How “Sacrificial Listening” Can Help Us to Love Our Muslim Neighbors

by Jennifer S. Bryson

What would it mean for Christians to make listening a cornerstone of Christian-Muslim relations? David Vishanoff calls this “Sacrificial Listening.”

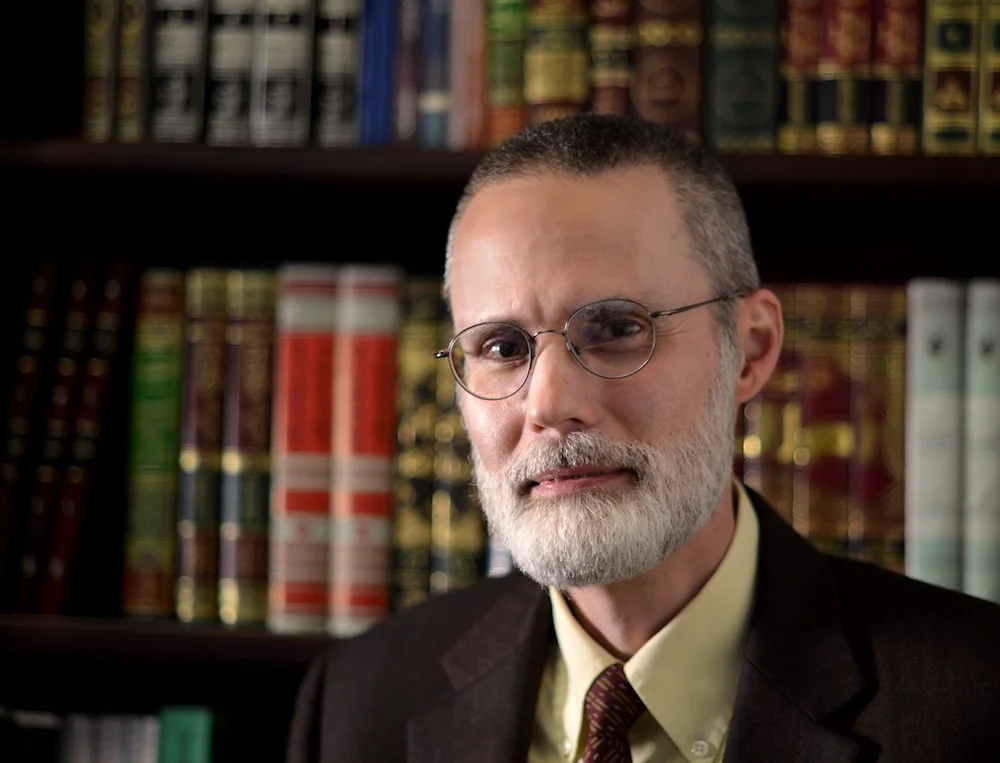

Vishanoff is a Professor of Religious Studies at Oklahoma University. He grew up in France, where his parents were Christian missionaries, and he attended Gordon College.

In an 18-minute talk (00:14:00-00:31:48) hosted by the Veritas Forum, Vishanoff challenges his mostly American, non-Muslim audience to reframe their approach to others, particularly Muslims, in terms of “sacrificial listening.”

He observes that much of what he encountered of Christianity in his youth focused on proclaiming to others. Yes, that is one side of the coin, but not the only side. So he began to question, “Is that really a Christian relationship, in which we just talk?”

In this presentation he discusses how he wants his students to develop not only “speaking knowledge,” i.e. acquired information in their head about which they can tell others, but also “listening knowledge, the ability to listen really well to what a Muslim is saying” (22:30).

In my own work studying Islam and Muslims for over 25 years, I’ve tried to ask, “What do Muslims say about their own religion?” Vishanoff’s talk challenged me to push this further, to develop a specific type of “knowledge” that equips me to listen more closely and more deeply.

Vishanoff explains, “I want you to learn to listen so well that you keep on realizing that you didn’t quite understand and that you’ve got to revise your understanding” (23:09). This is what he calls “sacrificial listening.”

He is well aware that listening to another deeply can be unsettling. We may discover the inadequacy, or even absence, of our own understanding, and we may be led to see that what troubles us about another’s interpretation, for example, of their own sacred scripture, is something we ourselves do in approaching the sacred scripture of our tradition.

Does this include listening even, for example, to ISIS supporters? Vishanoff responds, “I want to listen to those people too...those are human beings too...that doesn’t mean that... that would be a comfortable listening...but that’s the commitment I owe to them as human beings.”

In addition, he wonders about those ISIS supporters, “Maybe they don’t even care whether I want to listen to them or understand them.” To this I would say to Prof. Vishanoff, yes, they do care whether you want to listen to them, to understand them. During the two years I spent as an interrogator at Guantanamo, one of the consistent experiences I had with the diverse detainees I talked with was that they wanted to be understood. A radical willingness and a deep capacity to listen to others can open pathways to communication, even in the most difficult circumstances. This does not mean that the conversation will necessarily lead to agreement. But at least there will be communication, and as a result at least the potential for some understanding. If we listen.

Listening deeply to others may not only extend our understanding of them, but also extend ourselves. Vishanoff identifies this as “the blessing of finding discomfort in listening to another human being or listening to scripture...” Later he explains, “It’s not that discomfort is... to be pursued for its own sake. But if that discomfort is helping you to listen to God better, or it’s helping you to listen to another human being better, then I think it’s a good thing.”

Crucially, Vishanoff centers “Sacrificial Listening” on loving our neighbors. “I want to love people for who they are, and that requires this ongoing process of listening sacrificially.”

Jennifer S. Bryson, Ph.D., is Director of Operations at the Center for Islam and Religious Freedom (CIRF) in Washington, DC.